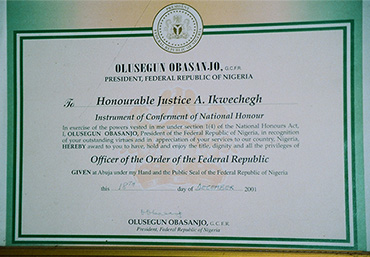

Justice Abai Ikwechegh (OFR)

[

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

From left to right: - Gordy Uche, SAN, Chief Chris Uche, SAN, Mr Uchenna Ihediwa (Attorney General, Abia State), |

|

|

|

Justice the first of its kind in Igbere and possibly Bende Local Government Area if not East of the Niger.

In a farewell bid, Barrister Ibe Ikwechegh, the first son eulogized his father with a promise that their house will never be overgrown by weeds, and poverty will never besiege the Ikwechegh family. Ikwechegh’s children including Dr. Obinna, Ms. Nnenna, and others were consoled by friends and well-wishers. The triangle of Igbere trailblazers: Dr. John I. Iboko, Chief Mazi, A. E. Ukonu and Justice Abai Ikwechegh have all gone to join their ancestors.

In the 1950s the photographs of these men used to be hung in classrooms at Igbere Central School.

A biography of Justice Abai Ikwechegh, written by Barrister Ibe Ikwechegh and published by the family is as follows: Abai Ikwechegh, OFR, was and is still my father. But when I think about a mentor, or a priest or an orator or a philosopher or an instructor and a teacher, I think about him, for he was all these to me.

Ikwechegh was born in 1923 to the late Chief Ogbonnaya Ikwechegh, a warrant chief and a merchant, and Oyiri Ikwechegh, both of Igbere, in the then Eastern Nigeria and now Abia State. He attended early primary school in Igbere and later went to the famous Hope Waddell Training Institute, Calabar.

His first career was teaching. He taught briefly at Abiriba, Ututu, Benin, Oka and finally at Enitona College Port Harcourt, with his bosom friend, Amadi Uche.

In October 1951, aged 28, he set sail aboard Elder Dempster’s MV Apapa to Liverpool, England, to seek training as a lawyer. He was on that journey with friends, Dan Akpan Eno and John Nnodi Odocha. He arrived on the fifth day of November 1951 and was received by his friend Kalu Okpan Anya. Together, both young men joined Edem Koofreh at 16, Priory Terrace. It marked the beginning of Ikwechegh’s profound journey of life.

Ikwechegh enrolled with the Kensington College of Law. He no sooner got integrated into religious and civic activities of his new environment. He joined the Methodist Church at West Hamstead and sang in its choir. He also registered the next year to be eligible to vote at the Polling District F-Golborne Ward.

In 1952, Ikwechegh lost his sponsorship and the Home Office in London sought to repatriate him. He began to live in hiding and was desperate to find ways to solve his sponsorship problems. It was about that time that his friend, Echeme Emole, arrived London from Dublin, preparatory to be called to the English Bar, and took notice of Ikwechegh’s difficulties. Echeme Emole returned to Nigeria soon after and tried to rally support for Ikwechegh. The effort produced £300, which was deposited with the Home Office. Ikwechegh was free again but did not draw from this fund. To maintain his stay in England, he worked at Lyon’s Tea Shop as a porter, then as a bus conductor under London Transport Service at Hendon and at another time as a clerk with the London Postal Services.

Amid his financial difficulties, Ikwechegh carried on well with great courage and faith. His friend Roland Okagbue pulled him aside one day and said to him, “Abai, I admire your dignity of bearing.”

With dignity of bearing and abiding faith in God, Ikwechegh completed his studies and was called to the English Bar in 1955. He was of the Lincoln’s Inn, Barrister at Law. In his diary, which survives him, he recorded on the night of the call, thus; “Lord, uphold me in the common strife, give me the grace to work and plan; And in the market place of life, O keep me, Lord, an honest man.”

On August 23, 1956, much the same way as he left the shores of his fatherland, Ikwechegh again was on board Elder Dempster’s MV Accra sailing from Liverpool to Lagos. There were with him on board other returnee barristers, Gregory Obiamiwe and Rufus Ogbobine.

Ikwechegh entered in “the market place of life,” joining his old friend, Kalu Anya, who had returned a year before, in his law practice at Aba. Shortly after that, he opened in 1956 his law offices, also in Aba, named Trinity Chambers. He practiced extensively in the eastern parts of Nigeria and in the southern parts of Cameroon.

On the bidding of a merchant friend, Ogbogu Nyama, Ikwechegh struck a deal with another lawyer named L.O.V. Anionwu Esq. to take over his practice in Jos. There he made friends such as S.D. Daas, A.F. Dabiri, Jimmy Ezekwe, Kayode Eso and G.C. Agbakoba. He enjoyed practice in Jos and found keen interest in criminal defence. Few of the notable cases were Haco Ltd v. Udeh (1959) NNLR 61, where he argued albeit unsuccessfully that the rule in Smith v Selwyn dictates that not only would prosecution have begun but must have concluded before felonious allegations could ground a civil suit. He made again the same type of ingenious contention before the Federal Supreme Court in Elechi v. The Queen [1958] SCNLR 321. Again, in Ogbu v. The Queen [1958]SCNLR 344, Ikwechegh was able to convince the Federal Supreme Court presided by Lionel Breth F.J. that evidence of an accomplice cannot provide the standard of corroboration required for a conviction.

In 1960, Ikwechegh learnt that the Penal Code was to be introduced in Northern Nigeria. He did not know how that would pan out with him already carving a niche as a criminal defence lawyer. He always believed that he would practice extensively and go to the bench but this was happening at a time when he was yet unqualified to go to the High Court. He discussed his predicament with Justice Jones before whom he had severally appeared. Justice Jones encouraged him that, rather than wait to be qualified for the higher bench, he might as well go to the magistracy.

In 1960, Ikwechegh was appointed a magistrate of the Eastern Region. He served in Port Harcourt, Onitsha, Ogoja, Abakiliki, Enugu, Umuahia and Aba.

His prominence began with his years as a magistrate. He would arrest a reckless driver and try him by himself. His simple explanation to the authorities was that he saw somewhere in the Laws saying that a magistrate could arrest for an offence committed in his presence and try such one as though he had been arrested and brought by another and that even if the power was seldom exercised did not minimize it. Again, he would test the limits of the law and sit on a Saturday to decide criminal cases.

There were indeed several attempts to stop him from these novel practices, including an order from the headquarters in Enugu barring him from criminal trials. He also received no further promotions as a magistrate. It was believed that the non-promotion was not unconnected with what was by then perceived as his recalcitrant behaviour. But, suddenly, in 1967, he was promoted with one step skipped. He later learnt that Justice G.C. Nkemena had pressed it upon Sir Loius Mbanefo that he ought not to be punished for doing what he conscientiously believed was a judicial function.

After the civil war, there were strong rumours that he was being considered for appointment as a High Court judge. In 1972, things came to head by Gazette No. 6, Vol 59 of 1972; Ikwechegh was appointed a judge of the East Central State of Nigeria along with Anthony Ijoma Aseme, T.C. Umezinwa, Emmanuel Araka Q.C. and Roland Okagbue.

It took two decades after his appointment as a judge to learn that the then Attorney General of East Central State, Mr Philip Nnaemeka-Agu, had recommended him for the position to the Administrator, Mr. Ukpabi Asika, who in turn sent his name to the Supreme Military Council. Nnaemeka-Agu had told the Administrator that Ikwechegh would bring glory to the State’s judiciary but warned him that he would not “dance” to the executive. Ikwechegh and Nnaemeka-Agu interacted closely when the later was subsequently appointed a Judge but Nnaemeka Agu never mentioned a word on the favour.

Ikwechegh served as a Judge of the East Central State until 1976 and was transferred as Judge of the High Court of Imo State. In December 1977 acted for the first time as Chief Judge of that State and would so act in subsequent years and at various times.

He was appointed as a Justice of the Court of Appeal in 1982. He declined this appointment and considered that he was more useful to the legal system as a judge of first instance. Again, he believed that some persons did not want him as a Judge in the state and wanted to despatch him out in the guise of elevation. He quickly wrote a protest letter to the then Chief Justice, Fatai Williams. Justice Idigbe invited him to have a word with him on the development. It was when he went to answer to Justice Idigbe’s invitation that he learnt for the first time that it was Idigbe that had recommended him to go to the Court of Appeal. Idigbe said to him, “I know you by reputation and thought that you should be working your way up to join us here”. Ikwechegh was later sworn in as Justice of the Court of Appeal with Justices, B.B. Pepple, Ephraim Akpata, J.H. Omolulu Thomas, Michael Ogundare, Sani Aikawa, Ibrahim Sulu Gambari and Umaru Abdullahi. Ikwechegh served and retired voluntarily from the Court of Appeal in 1988

Beyond his services in the Court room, Ikwechegh served his nation in other capacities. In January 1976, the East Central State Government appointed Ikwechegh to chair the Administrative Tribunal to investigate the circumstances which led to the Execution of Contracts for Data Processing Equipment. In 1978, Ikwechegh was appointed as one of the Chairmen in the Land Acquisition Control Tribunal which was as a fall out of the Land Use Act. Also in 1978, a Panel on Chieftaincy Disputes in Imo State was inaugurated and Ikwechegh was appointed to this august panel which was later known as the Ikwechegh Panel on Chieftaincy Disputes. He was also in 1978, appointed the Chairman of the Governing Council of the College of Technology, Owerri, now known as the Federal Polytechnic, Nekede and years after was appointed the Chairman of the Governing Council of the Alvan Ikoku Federal College of Education. He served his church, the Presbyterian Church of Nigeria as Chairman of the Board of Church Life.

Altogether, Ikwechegh spent his years as a Judge, family man and gospel teacher in revealing his discipline, his philosophy, his faith, his creed and his worship.

In his first public speech ever as a judge, Ikwechegh said “In its origins, this profession was noble, and it was honourable. When men bear true allegiance to its ethics and observe the accepted and decorous usages of this profession, it still shines as a field of endeavour for large hearted, illustrious, noble and educated breed of humanity, then the men and women who defend and protect the liberties and privileges of their fellows show themselves both honourable and learned. But some persons in the profession are not at all jealous of their reputation and with an eye to wealth easily and quickly got, bring dishonour to the profession.”

He indeed bore true allegiance to his judicial ethics, did all in his powers to observe and to preserve its decorous usages and shunned every passion for easy wealth.

Ikwechegh as a judicial officer thought that a Judge’s undue association would predispose him to influences that might jeopardise his judicial creed. In his 1978 address to newly appointed magistrates, he said “It is not expected that a good judge would circulate as freely…He would not be found in the usual haunts of his brother men. If he were so found, his reputation would be in jeopardy for in human nature, he would be called upon sometime to requite favours.”

Indeed, some of these peculiar creeds robbed him of all that effervescence, which can only be found in the midst of ‘fellow boys’ and left him almost a recluse.

Ikwechegh thought that a judge showing himself to love wealth invites entreaties which may be unsavoury, In August 1978, in a paper he presented titled ‘’Becoming a Magistrate’, he said to them “A magistrate and even the judge is vulnerable in his standing as a man on the bench, if it is known that his ambitions for wealth are beyond what he can legitimately achieve by orthodox means. Nobody should court poverty. But avarice is so very unbecoming of any person holding a judicial office. It leads very quickly to open corruption and the lowering of the tradition and standard.”

Ikwechegh lived to this creed. He led a simple life, lived in a modest home and even as a Judge in the 70s and 80s drove himself in his 504 Station Wagon.

Yet his lifestyle did not bother him. He believed that it was the price for a noble life which he says demanded “sacrifice of our self-assertiveness, if not the life itself.” He believed that there was something very powerful in humility for which he thought that many have become incapable. For when in 2003, he addressed a group of lawyers, he said to them “Humbleness has no constraint, no revulsion aspect; yet, it has all power: for it is of God. The humble, non assertive personality appears not of much esteem in the common judgment of his fellows; for the world loves the spectacular.”

As a judge, he had his eyes fixed more upon justice than upon the raw letters of the law. If he had any dilemma as a judge, it was to choose between his fidelity to the law and his fidelity to justice. For instance, he believed that one should not arm twist his opponent by defeating his move to terminate a proceedings for lack of diligent prosecution merely by filing ahead of such a move an application under the Rules of Court for stay. And so in Ogiri v. Idu (1972) 1 ESCNLR, he decided that a plaintiff who had treated his action with levity and had shown apparent want of eagerness to prosecute the same could not defeat the defendant’s application to strike out his claim by bringing a motion at the eleventh hour for extension of time even though such motions were supported by law.

Much later in his life, he proposed to find a way to do justice for litigants whose properties have been compulsorily acquired by the military government and who were destined to get no redress because of ouster clauses. He would in spite of the ouster clauses in those Decrees, assume jurisdiction and hold that part of his judicial function was to examine a case and be sure that the acquisition was legally made and only upon such finding would an ouster clause become operative.

Besides his judicial method and personal philosophies, Ikwechegh spent his years after retirement applying himself in deeper search for truth and the purpose of Man.

He thought that a fife of of meaning is that which fuses with the divine and accordingly wrote; “Each worships regularly at the shrine of individuality. He must be the first and hold the foremost place. But this is not personality. Personality is often lowly, but strong. It merges with the spirit, which is the foundation and base of all good”.

For many years preceding his death, Ikwechegh would spend hours, days and sometimes months in solitude and do nothing but contemplate God.

On the night of Saturday, 10th October 2020, a night vigil was held for Ikwechegh in which he and his family worshipped and prayed that he departed in peace. He was thankful and raised his left hand, a sign that he appreciated this profound session. Ikwechegh passed on the 12th October 2020 at the age of 97.

He loved God and insists that he would rather please God in all that he did. He loved his family and taught it by example. He loved his profession and guarded its tenets jealously. He loved his nation and would argue that if one serves his nation and bears true allegiance to it by upholding its honour and glory that such a person, whenever he or she dies is as good as dying for Nigeria. Shall this be the criteria, or at any rate part of it, then Ikwechegh could be said to have truly died for his Nation.

Justice Abai Ikwechegh would be remembered as a public person because of his many services to the community and multiple appointments. He was at the same time a private and reclusive person. He was brave, courageous and fearless to the end, but at the same time he was a shy and dignified man.

He left behind, a loving wife, Chief (Mrs) Mercy Ikwechegh and six children who worshipfully honoured him. He left behind his hand written notes of adoration which runs into thousands of pages and several unpublished Christian literatures and sermons. He left behind, a prodigious history of one who experimented the word of God and kept faith with his personal and judicial creed.

Those of us who knew him and are loyal to his lifestyle find his life to be an unending lesson note.

Fare thee well courageous Judge and teacher

Farewell thee well, servant of God

Fare thee well great father.

• Chief Ibe Ikwechegh,

Amankalu, Igbere

Legal Practitioner and Executive Secretary at Indent Consult